Malcolm Holcombe: A Remembrance

A few days ago, on March 9, 2024, my buddy Malcolm died.

I suppose it’s not right for me to call him my buddy because, in truth, we were not close. Not in the traditional sense of the word, anyway.

He and I were only in each other’s presence a handful of times and spoke on the phone perhaps another handful. I’d never been to his house, and he didn’t know my middle name. (But then again, that shouldn’t be surprising, as many of my good friends don’t likely know my middle name.)

And yet, I thought of us as buddies from the first time we crossed paths. It’s hard to explain why, but for some reason, it just seemed natural to do so.

Malcolm’s reputation preceded him. For someone such as myself who’s spent an inordinate amount of time contemplating the magical, mystical art of songwriting, Malcolm was something of a little-known but mythical figure in that world. A steely-eyed, cagey, and volatile dynamo of devilishly intricate and deceptively accomplished acoustic guitar technique, inward-looking, gruff (and almost feral) vocals, and declamatory, often opaque lyrics that straddled the (rarely-straddled) line between fiery, Old Testament-style admonitions and fiendishly clever C&W double entendres and witticisms.

A perennially scruffy, often unshaven, and reliably, loveably disheveled minstrel with long, thinning, wispy hair, a wizened, world-weary countenance, and a penchant for oversized, utilitarian work clothing that reeked of tobacco smoke, Malcolm would often nervously avoid eye contact for minutes at a time during conversations, only to suddenly and unexpectedly crane his neck up from staring at his lap (or the weathered leather of his dusty, creased boots) to fix you with a piercing look. He did this to emphasize a particular point or simply to let you know you’d misunderstood him – or perhaps inadvertently crossed a line of conversational propriety.

Then again, that also occurred when he could not help but let out a cautious but hearty laugh that was equal parts guilty cackle and hacking cough.

Maybe it was the fact that he and I had been raised and grown up less than 90 minutes from one another in Southeastern Appalachia (he was in the tiny Blue Ridge Mountain town of Weaverville, less than ten miles from Asheville, North Carolina, and I in the small, industrial mountain city of Kingsport, Tennessee) – and that as a result we could simultaneously and instantly recognize the tell-tale dichotomy of beauty and ugliness, of gentility and loathing, of salvation and damnation we’d both been unceremoniously steeped in since birth.

Or maybe I’m overthinking all of this, and we just got along from the get-go, as some folks do, for reasons unknowable. All that mattered was that I felt a kinship with him by the end of our first brief conversation, and it seemed the feeling was mutual.

We first met in person almost twenty years ago, in August of 2004, under fluorescent lights in the minimally appointed auditorium of the Wesley Monumental United Methodist Church in historic downtown Savannah, Ga. Malcolm had been booked to play a short solo set there as the headlining act on a long-running monthly, multi-artist bill of acoustic roots musicians known as the First Friday for Folk Music. Sponsored and run by the Savannah Folk Music Society, a volunteer-based non-profit organization devoted to promoting traditional, acoustic music and singing styles that included so-called Old-Time music (often geared toward traditional contra, square, and buck dancing), fondly remembered tunes from the 1950s and 1960s U.S. folk revival, Celtic, Scottish and Anglican balladry from generations (and sometimes centuries) past, and – from time to time – contemporary acoustic singer-songwriters working in the loosely-defined “Americana” genre-blending country, Western, blues, rock and pop.

When I’d heard he would be featured at that month’s installment of this concert series, I’d immediately sought out his booking agent (or publicist, I forget which) and inquired about the possibility of conducting a short phone interview with Malcolm. The interview was to appear in the pages of Connect Savannah, the free alternative-weekly paper for which I served as Music Editor (meaning I was responsible for writing advance features on noteworthy live shows in our area). Within a few days, those arrangements were squared away, and – from my end of the call at least – the resulting conversation was fascinating. Toward the end of the interview, as we said our goodbyes and I thanked Malcolm for taking the time to answer my questions, he said simply and quietly, “This was a good talk, ya know? Some of ‘em aren’t. I sure do hope we get to meet each other in person one day.” I had already planned to attend the show and told him I would most definitely be there.

When I entered the modest environs of the church’s somewhat outdated auditorium, the near dichotomy of the scenario that would soon unfold was striking. The first visual clue was the ancient folding card table at the back of the room, which served as a makeshift concession stand. Manned by a couple of elderly volunteers, the offerings were slim but notable: cans of soft drinks and plastic bottles of water kept cold in an ice-filled cooler, a few assorted candy bars, and four of five Ziploc bags, each containing a handful of tiny – likely generic – store-bought cookies. It was all very quaint. A descriptor I had not previously associated with Malcolm’s intensity, both as a person and as a performing artist.

After a succession of short opening sets by locally-based performers, most of whom might politely be termed “sincere enthusiasts,” Malcolm took to the stage armed only with a quite broken-in and visibly well-loved acoustic six-string guitar to perform a slightly longer set of his original material. This would close out that night’s installment of this beloved, family-friendly (meaning an alcohol-free, G-rated, all-ages-admitted show with only a voluntary donation of $2 suggested, but not even required) event.

The impressively wide age range of the small audience was perhaps from eight to eighty years old, and the mood of the entire evening up until that point had been exceedingly sedate and resoundingly uplifting. If memory serves, a spirited, decidedly unironic singalong of “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” or “If I Had a Hammer” had already occurred. In other words, this was Christopher Guest’s side-splitting improv-comedy feature film A Mighty Wind made flesh, only slightly more than one year after that Oscar-winning sendup of the traditional, staid American folk music community had subjected sincere yet somewhat shopworn organizations just like this one to withering – yet loving – mockery.

However, within thirty seconds of Malcolm perching himself precariously on the edge of the old metal folding chair that had been placed at center stage for him, it was as though the entire room, nay the whole church, had been struck out of the blue by a meteor and tilted on its axis. Gone were the lyrical platitudes, the dulcet vocal tones, and gently strummed guitars playing major chords. In their place, a litany of harsh, sputtered paeans and jittery, fragmented sermons – all delivered with the fire and brimstone of an itinerant tent revival preacher from the 1940s, filled with the Holy Spirit, or, at the very least, the amine β ring. He lit into his first number like an erratic vulture beset by Galvanism, or – perhaps more appropriately – like Guy Clark set astride a flickering, death-defying Kenneth Strickfaden contraption. The foot-stomping, head-banging, and torso-flailing ferociousness that I would soon learn occasionally defined Malcolm’s performances were in perhaps the starkest of all possible contrasts with what had come immediately before on the very same stage. Some in the crowd (such as myself) sat spellbound and in awe at the bewildering ease with which Malcolm deftly shifted back and forth from melding deeply poetic lyrics and graceful, complex guitarwork with such animalistic fury – often in the course of the same song. Others seemed utterly confused and more than a bit unsettled by the raw, unbridled passion pouring from this diminutive figure with a profound street urchin vibe.

I, for one, was in heaven. This was the sort of gifted artist I lived to share a room with and felt blessed to witness demonstrate their gifts.

This is the song that Malcolm opened his Folk Music Society set with, and if anything, it looked and sounded much more intense than this performance from around six years later.

After the show, I approached him gingerly but excitedly, still reeling and energized from the alchemy that had just taken place in front of me. And it was then and there that the die was cast.

Over the following years, I would interview Malcolm a few more times and be lucky enough to see him perform live and catch up with him a bit whenever our schedules aligned. I also became acquainted with his wonderful wife Cyndi, who served for decades in various capacities – as his manager, booking agent, and (often) his road companion and minder. But perhaps more than anything, his booster. And his protector. It felt like Malcolm needed a good bit of both of those last two.

By the time we became familiars, he’d already “lived a life others throw away nightly,” as Lou Reed once sang of his friend and mentor, the late, great Doc Pomus – another genius songwriter who may have been too good for this world. Tales of Malcolm’s troubles (and, with them, his troubled behavior) were legendary. And they followed him around. Not just the troubles but the tales as well. I got the impression (from anecdotes I’d read or were shared privately with me by those who knew him far longer and far better than I) that he sometimes felt somewhat inclined to live up to these tales. While at other times, it seemed he’d gladly jump a half-assed rocket-powered motorcycle over Snake Canyon if it meant outrunning the razor-sharp talons of his myriad of past addictions and indiscretions.

How bad did things get?

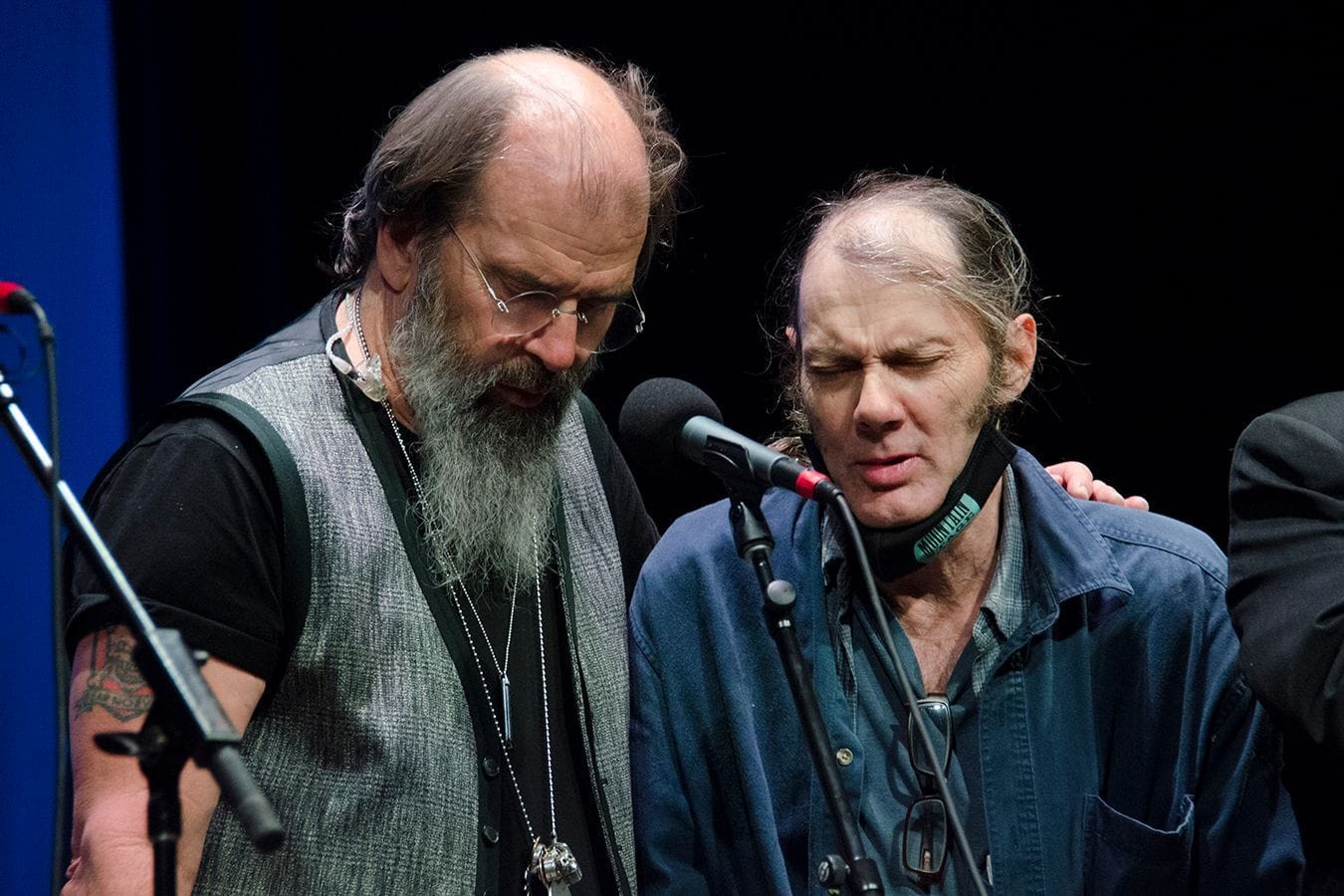

None other than fabled Texas troubadour Steve Earle (himself no stranger to the inevitable outcomes of decades of self-destructive, intoxicated, antagonistic or simply emotionally unstable behavior), the man who once publicly stated, “Townes Van Zandt is the best songwriter in the whole world, and I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my cowboy boots, and say that,” was also reported to have once said of Malcolm (another artist whose talents he openly admired tremendously), “(He’s) the best songwriter I’ve ever had to throw out of my studio.” Which, if not apocryphal, speaks volumes about the level of shit that Malcolm was capable of stirring up if he felt like it.

However, it should be known that despite decades of severe physical and mental strain due to heavy misuse of hard drugs and alcohol, Malcolm got himself clean and remained sober, abstaining from intoxicants for the last 20 years of his life. Yet another triumph for this somewhat superhuman figure.

Malcolm valiantly battled cancer for years leading up to his untimely death. That, combined with the deleterious effects of the COVID pandemic on the live music industry, resulted in him making very few public appearances for quite some time. However, he soldiered on and – as many musical artists worldwide did during the lockdown – offered up a surprisingly large number of no-budget, DIY streaming concerts online. These homespun affairs reliably occurred in a small shed on his North Carolina property. But, even after touring had resumed in most respects for most performers, his own health concerns prevented him from hitting the road in any meaningful way. And so, these intimate streaming events continued right up until the winter of 2023.

What were initially placeholders for canceled tours eventually became substitutes for even the hometown public gigs he was simply too weak, fragile, or immunocompromised to attend.

This was, quite literally, the only way that he could continue to regularly perform for – and interact with – his fans. The only silver lining to what must surely have been a frustrating and dejecting situation for him was that Malcolm wound up creating a phenomenal resource and archive by holding these live, streaming events that remain online. Now, dozens of informal, candid concerts by him are available for anyone to find and watch. They demonstrate the scope and breadth of his unique and awe-inspiring abilities, even as they inadvertently chart the inevitable ups and downs of his physical condition and stamina, ravaged as he was by illness.

I was so overwhelmed by the totality of these events as they were initially taking place that I have only seen a few of them. I hope they remain on YouTube in perpetuity, as I plan to take an extended period – perhaps years, even – to view them all in the order in which they were recorded. That way, it’s almost as if I can keep Malcolm alive. As a living, breathing, performing artist, playing just for me, every once in a blue moon, for the next decade or more (should I be fortunate to live that long, myself).

I encourage anyone reading this remembrance inclined to understand and appreciate more about him and his songs to consider doing the same.

This is one of Malcolm’s shed shows. The second song in the set is called “Cool In Savannah.” I think I know what precipitated him to write that one, but even if I’m right, it’s not for me to say.

A few days after word of Malcolm’s passing spread, none other than the Country Music Hall of Fame released a statement on his life. It read in part, “Enigmatic, gifted singer-songwriter Malcolm Holcombe… died of respiratory failure on March 9. He had been ill with cancer and packed a lot of hard living and singular songwriting into his sixty-eight years.”

Enigmatic and gifted were right.

The statement continued thusly, “Holcombe was held in high esteem by some of the most admired songwriters in American music, including Lucinda Williams, Steve Earle, David Olney, Mary Gauthier, Tony Arata, Darrell Scott, and others.”

Truer words were never spoken.

It was a lovely and well-composed piece of writing, which neatly summarized the arc of his career and mentioned his immense skills as a flatpicking guitarist and his “brooding, sandpapery” voice. It made it easy for the uninitiated to immediately comprehend that he was an artist worthy of respect and investigation. But I could not help but feel that it lacked, I don’t know… Something.

I suppose I found that something by happenstance a day later when I spied a short, off-the-cuff remark written on social media. Posted perhaps thirty comments down underneath a shared article about the sad news, it read: “(I) saw Malcolm many times when I lived in Asheville. It was said that you weren't a musician in Asheville or Nashville if Malcolm hadn't severely pissed you off at one time or another. But, (that was) just another facet of (being) an amazing writer and observer.”

Hear, hear.

In memory of Malcolm, I chose to revisit the first interview I conducted with him, and I will share it with you now below.

While it originally appeared in print on August 4, 2004 (two days before he would make what I believe to be his Savannah-area debut at that First Friday for Folk Music I spoke of above), the version I am including here has been expanded, amended and re-edited by myself on March 14, 2024. Think of it as a Director’s Cut.

If any of you have stories or memories about Malcolm or simply thoughts about this piece you’d like to share, I’d love to hear them, and perhaps other Wicked Messenger subscribers would as well. Please leave a comment underneath this post, or hit reply and send me a note. That’s what we’re here for.

Thanks for reading.

2004 Malcolm Holcombe Interview

“I don’t think there’s much skill in what I do.”

By Jim Reed

Malcolm Holcombe may be one of the best American songwriters you’ve never heard.

Or heard of.

While well-known in the types of circles that follow such things as deeply personal singer/songwriters, he’s virtually anonymous to the vast majority of the record-buying public. That’s a true shame, as luminaries in his field, such as Steve Earle and the Grammy-winning Lucinda Williams, highly revere the 48-year-old guitarist. In fact, it was only through the almost constant private (and public) pleading of those two stars that Holcombe’s 1996 Geffen Records debut A Hundred Lies was finally released in 1999 after sitting unceremoniously on the label’s shelf for more than three long years.

The unfortunate by-product of a corporate merger was a newly installed team of A&R personnel, which callously tossed aside the artist’s first real chance at a national audience by deeming it “not commercial enough.” Viewed as anything but a priority by the company’s new owners, A Hundred Lies wound up as collateral damage and – one can only imagine – a significant tax write-off.

It also hamstrung Holcombe’s career and left him swinging in the breeze, unable to share his excellent album with anyone save for his peers and fans in the industry who’d heard leaked copies and were determined to shame Geffen into loosening their grip, for the sake of the song.

However, after a tiny niche imprint finally got the message, squeezed a license out of Geffen, and pressed the record, it quickly earned a rare four-star review in Rolling Stone from no less a finicky scribe than David Fricke, who proclaimed it one of the finest albums of its type in decades.

A modicum of underground notoriety followed, but even after that great stroke of good fortune, the mercurial Holcombe (whose measured, poetic discourse and still-strong Weaverville, North Carolina drawl at times summons unavoidable comparisons to Billy Bob Thornton’s backwoods-y character in the film Sling Blade) remains a figure stuck on the far edges of the Americana scene.

After enough hard times and shady Nashville deals to fill a thousand tearjerkers, he now lives near Asheville in Swannanoa, North Carolina, with his wife and children. He tours infrequently but has released two subsequent indie albums, both lauded by critics worldwide for their haunting authenticity and intensely private and clear-eyed nature.

Known to be mesmerizing and unforgettable in concert (he's said to go from a whisper to a scream and has been known at times to prowl the stage with a simmering fury), he continues to write and perform – in the words of Fricke – “blues in motion, mapping (the) backwoods corners of his heart.”

Malcolm Holcombe spoke with me from his home in the mountains about his influences, his inspirations, and his abiding faith in the divine.

Long before you hit Nashville, you worked for years as a bar musician in the Tampa Bay area. Now, everyone I know who’s spent much time playing music in Florida has no shortage of strange tales...

You know what? Yeahhh... Uh... Very well said. Very well said. Yeah…

When A Hundred Lies finally hit the streets, you – and that album- were compared to '60s troubadours like Dave Van Ronk, Tim Hardin, and Eric Andersen and their recorded work. Would it be a mistake to assume you were already conversant with their oeuvres and were aiming in that direction? Or were those critics just hearing some of their own record collection within your songs?

You know, that’s flattering to me. I’m glad to hear folks mentioning mentors of mine. Tim Hardin, Tom Paxton and some of the folks that get mentioned... And in my mind, those ARE troubadours and folk musicians and songwriters. I don’t have any of their records, but I’ve heard their stuff for many years. Tim Hardin... those were beautiful, soulful, and real songs. So, to be compared to these people is really humbling to me. I don’t read that stuff, you know.

Are you ever surprised at some artists whose work is compared to yours?

I can understand that people dance to a different drummer, you know? Everybody has their own sounds in their head and their heart, you know... Somehow, they’re hand in hand, and sometimes they’re miles apart. I’m grateful that anybody would take enough time to listen and make a comment at all.

Is there anything you’ve listened to lately that occupies the same space in your hand and heart as your initial mentors?

Ahh... Good question! Well, Dave Olney’s still out there. Tony Arata is a songwriter… Aww, well, you know all about Tony – you’re from Savannah!

Yeah. He is sort of a favorite son around these parts. [Arata was born and raised in Savannah and hit it big by writing such number-one C&W hits as “The Dance” for Garth Brooks (nominated for the Grammy for Best Country Song) and “Dreaming with My Eyes Open” for Clay Walker. He is a member of the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. – Ed.]

He’s a wonderful gentleman, and when I moved to Nashville, he inspired me more than anyone in my life. He’s a dear friend and has helped me more than he’ll ever know – as a child of God, and as a human being on this planet, and as a songwriter. Just (through) his passion and his emotion and his truthfulness… He’s very humble. We’ve done some shows together, and we’ve got one coming up. And I think (as far as) anyone these days, he should be hand in hand with Tim Hardin, Tom Paxton, Burl Ives, you name ‘em. Right on down the line.

People say that he has a certain way about him.

Well, he almost ran me over in his Grand Prix in a parkin’ lot one time! When you don’t pave it, you get potholes, you know? But he stuck his hand out to shake mine just before he cut the wheel, you know. So, he’s a good driver in dirt parkin’ lots! (Laughs)

Bob Dylan’s esteemed 1970s sideman Steven Soles, who played with him on the Desire and Street-Legal and Live at Budokan albums, was your producer on A Hundred Lies. He’s such a talented multi-instrumentalist. What was he like to work with, for you as an artist?

Well, he’s a good producer. He stayed outta the way, and he called up some folks. He just kinda let it flow. We learned the songs while chain smokin’ and drinkin’ coffee outside his studio in Santa Monica. He was wonderful to work with and very positive. He and I and Greg Leisz [famed pedal and lap steel guitarist – Ed.] would just sit around together, and I’d show ‘em how the songs went. Then as soon as we had it, we’d go inside and cut ‘em.

I’ve heard you mention in interviews that you feel your talents are gifts from God.

Well, I think we’ve all got gifts that we’re given at birth, you know? Life is one. Now, what we do with those is a big responsibility – even if you’re pushin’ a pencil. I have taken advantage of that. I guess there’s some skill involved, but I don’t think there’s much skill in what I do. That’s just the way it is, you know? No man is an island. People call Him different names, but what I believe is that it’s a gift from someone bigger than me. So, it’s God. The big picture. I mean, The Man. Without bein’ ambiguous or too vague, it’s a very personal thing to me. To all of us. Whatever we do is our spirituality. I try to reflect that in some songs. They’re not contrived as much. That is, I try not to contrive ‘em. I try to make it at least as palatable as I can for my own self. I try to deliver. That’s my job, and it’s been my job for a long time. Sometimes I show up for work, and sometimes I don’t… I’m tryin’ to show up for work these days. I mean, if you’re gonna make a ham sandwich, well then make it! Make it the best that you can with what you’ve got. If you’re gonna eat it, eat it! If you’ve got any left over, you might wanna split it three ways. You could look around and see who’s hungry… Some of the songs ain’t pretty… Well, life ain’t pretty! Life isn’t a bowl of Cherrios! Or a bowl of cherries, or whatever… You know that yourself. Reality is not pretty. Sometimes it is pretty. The sun’s shining out here today.

Are you trying through the act of writing and performing songs to find the beauty in the ugliness? Does that make sense?

Yeah, it makes sense. But I’m not tryin’ to make a purse out of a sow’s ear. It’s a sow’s ear. Call a spade a spade, you know?

Member discussion